There is an idea within academic, commentary, and left-wing activist spheres which has come to act as the primary obstacle towards the development of revolutionary consciousness. This idea can be summarized as: “the most effective challengers to capital and empire are not worth taking example from.” Whether this idea is used to propagate the foundational left anti-communist myth (this being that Stalin ruined the Russian revolution), or one of the left anti-communist myths about today’s socialist experiments, its function is to sabotage the emergence of a vanguard. To target ideologically developing individuals who could otherwise become members of a revolutionary effort, and lead them to a stance that causes them to help maintain the existing social order.

When somebody has embraced this stance, they can decry the policies of the U.S. government all they like, and still inhabit this role as an obstacle towards the people’s victory. Such is what happens with the left-wing radicals who get successfully sent down the anti-China ideological pipeline. By anti-China, I mean more than when somebody is advocating for a militaristic policy towards the PRC. I also mean when somebody promotes debunked or unproven accounts of human rights abuses, something that even critics of the new cold war reliably do when they have a platform backed by capital. This self-reinforcing set of ideas, where the fundamental myths behind the war on China are affirmed within our discourse even by those who don’t want war, is made possible by the foremost left anti-communist notion of our time. This is the notion that the PRC’s system of government can’t genuinely be called socialist.

To take this position, one has to be coming from a place not informed by a dialectical analysis of history. The liberal view of China—which is to say the view that has an incentive to protect imperialist interests by devaluing imperialism’s challengers—looks at China’s elements of private enterprise, and concludes from this that China must not be a dictatorship of the proletariat. What’s revealing is that the types who take this stance predominantly don’t even care about establishing a dictatorship of the proletariat. They’re liberals who celebrate the fall of the USSR, and the massive social murder this led to, because they view any model of democracy which the bourgeoisie can’t domineer as anti-democratic. There are also the ultra-leftists who believe China was a dictatorship of the proletariat prior to Deng and Jintao’s reforms, but their view is the minority one, since most within their broader ideological camp think Mao was a “totalitarian.” Whether regular liberalism or ultra-leftism is the driver behind their statements, the perception they share is that China’s opening up its markets renders its socialism a fraudulent one.

This view is undialectical because it disregards what the market reforms have been leading up to this entire time. That being the reversal of the liberalizations which the country underwent, and the restoration of its more nationalized original model. Except because of those reforms, and the immense wealth they brought, this model will now have the economic basis to be sustainable.

The argument of these liberals is that China’s government can’t be trusted to allow such a dismantling of private business, because supposedly the integrity of the country’s ruling party became compromised when the reforms were implemented. If this were true, then China wouldn’t have responded to Washington’s provocations against it by embarking on just such a project to de-liberalize, and to more effectively counter imperialism in the process. The assumption of the anti-China left was that the country would never progress beyond the most privatized stage that it was in during the 90s and 20s, that its project to build up its productive forces could only bring a terminal decline of socialism within the country. Now that the war on China has prompted China to choose between liberalism and revolutionary politics, it’s shown to have picked the latter path. There are some liberals within the 90-million-strong Communist Party who seek to join the U.S. bloc, and to implement the Khrushchevite reforms the U.S. wants, but their side has lost.

The initial way China was compelled by Washington’s attacks to embrace a more revolutionary role was by adopting a highly assertive foreign policy. Since 2012, right after Obama’s “pivot to Asia” in which Washington began the new cold war, the PRC has been acting with the mindset that it must further its sovereignty, its security, and by extension its global standing. The liberals say this is nothing more than a rival imperialist project, but Xi Jinping has directly rebuked this charge, saying: “China will never seek hegemony, expansion, or a sphere of influence no matter how strong it may grow.” The type of influence that China has gained and will gain is distinct from a “sphere of influence” as Washington defines it, where a country increases its power not to cooperate with others but to exploit and subjugate them. The myths about China acting like this, promoted by supposedly subversive commentary sources like the Daily Show, are easy to debunk.

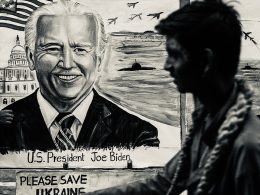

U.S. hegemony is the globe’s primary contradiction, the PRC is weakening U.S. hegemony, and the PRC isn’t creating a new imperialism by the term’s Leninist (as in materialist) definition. So this policy alone has given the country a greater revolutionary status than it had only two decades ago. China still hasn’t gone so far as to voice support for Russia’s anti-fascist war in Ukraine, like the DPRK has done. But China doesn’t need to be so vocal, nor send weapons into the conflict as Washington alleges, to assist in Russia’s effort at accelerating the U.S. empire’s downfall. It’s only had to affirm that Russia was provoked, while meeting with Putin about helping get Ukraine to agree to a peace plan.

The PRC has also grown more revolutionary in its domestic policies. Xi Jinping’s aggressive anti-corruption campaign was a prelude to the war China’s government has lately been waging against the country’s billionaires. Bloomberg wrote last year about one type of recent historical contrast that’s shown this increase in the Communist Party’s radicalism:

Cheers greeted China President Xi Jinping as he toured Beijing’s Renmin University of China in April, telling students and teachers: “We must continue to promote the modernization of Marxism.” Social science research, he said, should have “Chinese characteristics” and contribute to “China’s independent knowledge system.” It was a notable contrast to 11 years earlier, when Hu Jintao, Xi’s predecessor, visited the same campus, “listening carefully” to discussions on macroeconomics. That was in China’s boom years. The economy was growing faster than 10% a year, and private entrepreneurs in sectors such as real estate and technology operated with more autonomy than ever. Corruption and pollution were rampant. Karl Marx wasn’t mentioned. Now, Xi was meeting with two “political economists”—Liu Wei, the university’s president, and Zhao Feng—who blend Marxism with elements of Western economics. The visit highlighted China’s pivot to funding and supporting researchers who are suspicious of the power of private business, with some advocating barring private capital from entire sectors. The message was clear: In today’s China, Marxism is back, and investors had better take note.

This isn’t quite how a serious Marxist would portray these events, because those who properly grasp dialectics understand that whatever valid criticisms could be made of the Deng/Jintao era, Marxism was never truly not present within China. If Marxism had been successfully expunged from the party, its recent shift back towards nationalization, increase in penalties upon unethical business practices, and redoubling of efforts to foster class consciousness within government wouldn’t have happened. Post-Mao China has never been an equivalent of the post-Stalin Soviet Union, because Deng was not another Khrushchev. He didn’t make the party unable to ever again commit to class struggle, because he didn’t weaken the dictatorship of the proletariat like Khrushchev did in the USSR. The mechanisms for the proletariat to assert its dominance have still been in place.

Moreover, the Deng reforms themselves didn’t turn China into a neoliberal haven, but rather allowed for a controlled element of private business that existed alongside the state-controlled elements. Therefore the idea that China ever regressed back to capitalism is overly simplistic. As Invent the Future clarified in 2018, prior to when the nationalization reached its present intensity:

Although the number of employees of private enterprises has overtaken the number of employees of state- and collectively-owned companies, the basic economic agenda is set by the state. Private production is encouraged by the state only because it contributes to modernisation, technological development and employment. While some Marxists may insist that markets can have no place under socialism, it’s difficult to reconcile such a view with Marx’s own view of socialism as a transitional stage on the road to communism. China has proven in reality that it can use (heavily regulated) market mechanisms in order to more rapidly develop the productive forces and improve the living standards of its people. It will come as a surprise to many readers to know that public ownership continues to dominate in China. There has been very little in the way of actual privatisation, in terms of transferring ownership of state enterprises into the hands of private capital; indeed, the state sector is several times bigger than it was in 1978, when the reforms were launched. Rather, private enterprise was allowed to develop alongside the state sector, and has grown at an even faster rate than the state sector (bear in mind that it started from a very low base).

Even throughout the country’s past pollution crisis, healthcare privatization, and rise of a billionaire class, a basic proletarian democratic structure was maintained. A structure that the workers could use to undo the liberalizations when the right time came. Now that this time has come, the rich have been collectively losing hundreds of billions, at the same time the people’s living standards continue to rise following 2020’s elimination of absolute poverty within China.

The liberals will still say China’s new guiding class of Marxist economists can’t reconcile Marxism with the relatively open economy the PRC still has for the time being. Yet even when they’re proven wrong, and the economy becomes further de-liberalized, these dishonest actors will still say China isn’t building authentic socialism. We know this because even when these actors look at the DPRK, the socialist country that’s not had free market reforms and has developed the furthest towards communism, they still say Juche Korea isn’t a true example of socialism. Whether they say this because they’re NATO liberals, and believe the Orientalist myths about the DPRK being a “totalitarian monarchy,” or because they’re ultras, and reject Juche as a perversion of socialism, their essential sentiments are consistent. No country will ever be socialist enough for them, nor will any country ever be carrying out anti-imperialism in a way that they deem morally acceptable. Those who’ve set themselves up against China, Russia, the DPRK, and the other countries resisting U.S. hegemony have placed themselves on the losing side of history, letting the rest of the world progress without them.

————————————————————————

If you appreciate my work, I hope you become a one-time or regular donor to my Patreon account. Like most of us, I’m feeling the economic pinch during late-stage capitalism, and I need money to keep fighting for a new system that works for all of us. Go to my Patreon here.