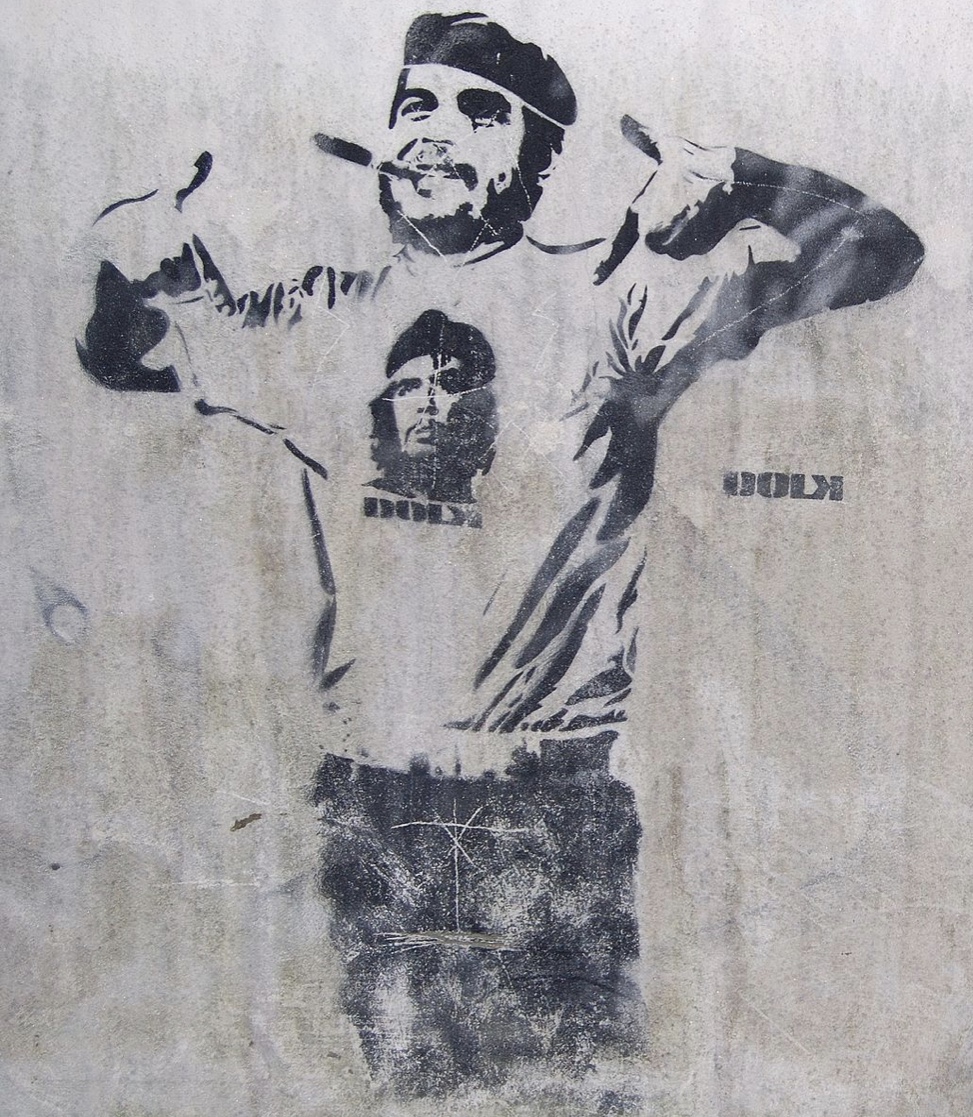

When one invokes the symbol of armed struggle which is Che Guevara, or invokes armed struggle as a whole, they must do so responsibly. If I were a movement wrecker, the only things I would say in this essay are the topic’s surface level facets. Those being that Guevara provided an example of a successful effort to achieve liberation from a violently oppressive government using the practical tools for the situation; that the methods of using the tools of one’s enemy against them which Che employed must be studied; and that the conditions in the United States are headed for a point where those methods will be necessary. All of these things are true. But to talk of the revolt Che waged, without covering the mistakes Che later made in attempting revolt, is to lead communists into replicating those mistakes.

Where Che went wrong, despite having gone so right within his efforts in Cuba, was partly in how he tried to apply his practice in Cuba to the distinct conditions within Bolivia. More than that, he tried to replicate only one specific part of his original mode of operating—that being to focus on military strategy—while overlooking the component of having an organized mass movement to back up the military actions. He assumed that if he established a revolutionary foco in Bolivia, the appalling conditions of the Bolivian people under their neo-colonial dictatorship would ensure his foco’s victory. But the physical isolation from the locals that his foco took on due to his prioritization of military strategy (in which he chose an inopportune location for reaching the people) doomed him. The dictatorship’s execution of him made him into a martyr, but he was still defeated.

These are the details in Che’s story that I dismissed during my early time as a communist, and that I couldn’t seriously analyze until I refined my initial understanding of what tactical revolt means. This understanding being that if a cadre gets the equipment and the training, it will be in a place to subdue the capitalist state, so long as it follows the model of asymmetrical warfare. This model can be summarized as: you win by outwitting the enemy, not by out-muscling them.

That idea is correct in itself, but it must be implemented along with the understanding that if you don’t have the people on your side, your revolt won’t get far.

What does it mean to get the people on your side? It means to educationally lift them up to the level of a cadre member who’s trained in Marxism; to aid them in getting connected to the labor organizations which they can use to strike or demonstrate in coordinated fashion; to build the connections with them that will allow your cadre, should it be sufficiently trained, to assume the duty of leadership. This duty will become necessitated by the popular demand for changes, changes which the capitalist state refuses to enact. That’s why Che described the guerrilla fighter as a social reformer; their role is to fight for the improvements in conditions which the people have assigned them to advance.

This is where the idea of using the state’s own warfare tools against it comes in. The capitalist state is brittle. It exists fundamentally in opposition to the interests of the people, and therefore must maintain a perpetual balancing act in which it’s foremost serving the bourgeoisie’s interests while keeping the people from rising up. During the era of neoliberalism, where capitalism has reached a stage in its decline in which the welfare state is no longer compatible with profits, this task has grown more difficult. The capitalist state has had to progressively drive down the living standards of the people, and in the age of Covid-19, war-related inflation, and climate disruption, this deterioration in our conditions is accelerating. The people’s discontent is growing all the time, threatening to morph into an unmanageable situation for the ruling class.

When will the situation become unmanageable? When the state can no longer manage to sufficiently frustrate revolutionary organizing via COINTELPRO tactics, or to sufficiently co-opt the people’s discontent by funneling it into the Democratic Party (as well as into the smaller controlled opposition strains). There’s sociological evidence that in our generation, the intensifying poverty and police brutality which the U.S. empire’s internal colonies are subjected to will provoke the most disenfranchised communities into an armed anti-police insurgency. But that won’t lead to revolution unless we’ve built the organizing structure and mass educational initiatives required to translate popular anger into revolution. The country has already undergone a revolt of unprecedented proportions, albeit an almost entirely nonviolent one; the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests were the largest demonstrations the U.S. has ever seen. But even that didn’t produce revolution, because the revolutionary infrastructure wasn’t yet in place.

Properly analyzing Che’s military theory isn’t merely a matter of recognizing his technologically outdated tactical advice, which I’ve done in the past. It’s also about recognizing that for the theory to be applicable, the people must be backing the military effort. Only when you’ve gotten that taken care of can you employ the beautifully empowering logic which is the essence of Che’s military theory, and which is objectively correct: get the state to overextend itself, and you’ll defeat the state by having it engineer its own downfall. Che described this in Guerrilla Warfare: A Method:

These dictatorships carry on within a certain “legal” framework adjudicated by themselves to facilitate their work throughout the unrestricted period of their class domination. Yet we are passing through a stage in which pressure from the masses is very strong and is straining bourgeois legality so that its own authors must violate it in order to halt the impetus of the masses. Barefaced violation of all legislation or of laws specifically instituted to sanction ruling class deeds only increases the pressure from the people’s forces. The oligarchical dictatorships then attempt to use the old legal order to alter constitutionality and further oppress the proletariat without a frontal clash. At this point a contradiction arises. The people no longer support the old, and much less the new, coercive measures established by the dictatorship and try to smash them.

This will be how the social contract which supports the state unravels in the USA. The revolutionary organizations will get too strong for the state to be able to co-opt or frustrate via reactionary intrigue, then the state will lean more onto its violent repressive tools. Tools that in the USA’s case will be imported from its imperial military occupations abroad. This provocation from the state will harm the state’s credibility among the people, leading to more being willing to back the revolutionaries.

The big qualifier to my discussion of guerrilla warfare is that we don’t know if, or to what extent, guerrilla warfare may be called for by our conditions. The U.S. is not like Cuba, or any of the other peripheral countries. Which is all the more reason to reject focoism. Yet we must be prepared for anything the circumstances might demand of us. We must get equipped and trained not because we dogmatically expect the revolutionary stories from other places to get replicated here, but because we can’t go without the tactical tools past successful revolutionaries have had at their disposal. The important things are that we don’t go on the offensive when the masses aren’t ready, and that we don’t refrain from going on the offensive when the masses are ready.

Should it come to the latter scenario, where such a confrontation becomes focal to the class struggle here (and I believe it will based on that evidence of a coming anti-police insurgency), we’ll be able to navigate the challenges this entails by referring to the central part of Che’s military theory. To the idea that it doesn’t matter how outgunned the revolutionaries are, because if they go by the warfare rules of both Che and Sun Tzu, they’ll be able to avoid getting wiped out by the enemy while manipulating the enemy into sowing its own demise. The key ingredients in this process are stealth within how one operates, discipline within one’s cadre, and care for winning and maintaining the people’s support.

By the nature of the enemy as a bourgeois, settler-colonial imperialist apparatus, it can’t fulfill any of these criteria. It’s a decaying state, its armed forces filled with working class people whose class interests go against that of the military they’re serving and who could largely defect in a revolutionary scenario. The people are increasingly against it. It will have to rely on massive, terroristic violence in its internal counterinsurgency, which will make it lose the masses. We’ve seen this in Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and the other places the U.S. empire has failed to subdue. If the revolutionaries here act competently, the U.S. empire will fail here in the same way.—————————————————————————

If you appreciate my work, I hope you become a one-time or regular donor to my Patreon account. Like most of us, I’m feeling the economic pinch during late-stage capitalism, and I need money to keep fighting for a new system that works for all of us. Go to my Patreon here.