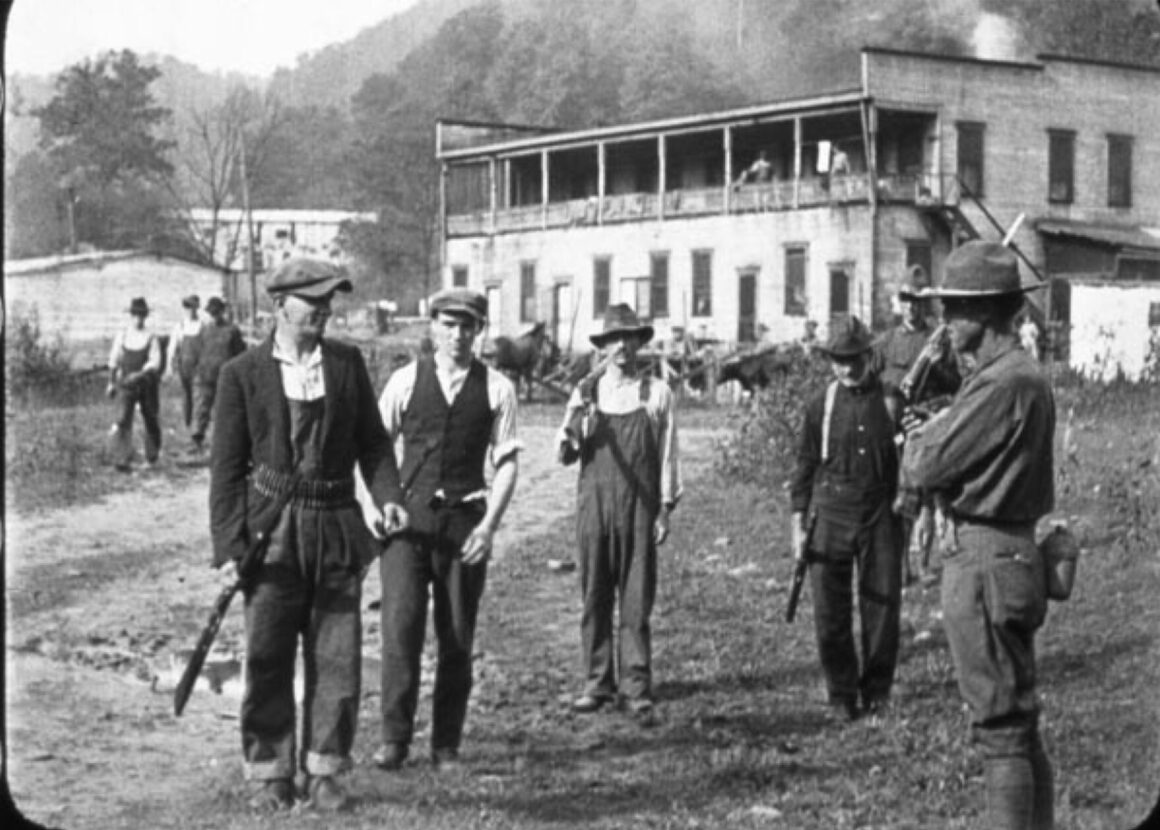

Above: from the West Virginia mine wars, one of the many rural labor developments in the country’s past

This analysis that I’m putting forth about the conditions of my own region—the Pacific Northwest—applies to every other rural area throughout the country. During my investigations into what will happen to my home during the region’s coming great earthquake, I’ve learned lessons about the character of rural America. Lessons which U.S. Marxists must apply to their practice, or else end up surrendering this land’s future to monopoly finance capital.

Finance capital’s liberal agents have sought to propagate the idea that the country’s rural areas are so backwards, so deplorable, that there isn’t hope for them to contribute towards progress. This is the prejudice that the Democratic Party has embraced, and even many leftists who try to distance themselves from the Democrats have followed them in dismissing the rural masses. It comes not from a true investigation of our conditions, but from an effort at rationalizing opportunism; the modern left’s geographically limited practice will never be effective at challenging our social system, so the upholders of this practice need to create a narrative about why it’s supposedly necessary. This is the narrative that those beyond the liberal bubble are fundamentally reactionary, which forsakes a serious analysis of our conditions.

As the communist Phil A. Neel writes in Hinterland: America’s New Landscape of Class and Conflict, the accurate image of rural America

…is not the one favored by the metropolitan think piece, which sees racial resentment as the natural outcome of such “economic anxiety.” Instead, traditional methods of transforming class antagonism into racial difference are beginning to reach a sort of saturation point, as unemployment, mortality, and morbidity rates all start to overspill their historically racial boundaries. The effects of this are extremely unpredictable, and political support will tend to follow whomever can offer the greatest semblance of strength and stability. But the left is neither strong nor stable. Liberals ignore these areas because low-output, low-population regions very simply do not matter much when it comes to administering the economy—and that is, in the end, what liberalism is about. The far left, on the other hand, has long been in a state of widespread degeneration. It has retreated from historic strongholds in the hinterland (such as West Virginia, once a hotbed for wildcat strikes and communist organizing) to cluster around the urban cores of major coastal cities and a spattering of college towns.

The need to grow beyond such nationally divisive thinking, where “socialists” deny the revolutionary potential of tens of millions of people, is illustrated by the economic collapse of the rural communities. A collapse which will be greatly sped up by the region’s mega-quake, depending on whether it comes prior to when the workers have gained power.

As I’ve researched the Cascadia subduction zone, the fault line that will create a rupture of the same scale as the 2011 East Japan earthquake, a question that’s inevitably come up has been: what effect is it going to have on history? Things aren’t going to simply go back to the way they were. Of course, the Cascadia quake doesn’t need to happen for the region to be in crisis. California is already experiencing a drug epidemic, extreme inflation, and other symptoms of capitalist collapse. Global warming is bringing enough fires, heat waves, and floods for internal migration and infrastructure breakdowns to be underway right now. If the quake does come within the next few decades, though, it will show just how inadequate our social systems are. The country will be in a more advanced phase of its breakdown than it is now, multiplying the risks from Cascadia and all other potential disasters.

Even though the authorities are trying to make improvements in preparedness for the event itself, the broader socioeconomic situation is worsening as capitalism contracts, and as our ruling elites force more people to the economy’s peripheries. This heightened danger brought by growing class inequality is present throughout the entire West Coast, whose southern half is set to experience its own extreme quake when San Andreas ruptures. Because of how widespread these geological catastrophes are going to be, that exclusionary liberal attitude towards the rural will be challenged by these events if they come before the revolution. And even if they don’t come that early, we’re already seeing our government incrementally abandon this region, along with all the country’s other rural sections.

My Northern California community is one of these places which the ones with the most power consider to be expendable. And because the highest levels of capital view places like it as such, fascists have been able to gain a growing amount of influence within its surrounding locales. My town is part of the “empty coast” between San Francisco and Portland, an area that’s surrounded by mountain ranges which have made it difficult to build the infrastructure needed for large-scale migration. Because of how small this region’s population is—with its biggest city, Eugene, being inhabited by less than one-fifth of a million—a contradiction has arisen between it and the vast metropolitan centers which surround it. Over the decades, many residents of this region have felt that the Oregon and California state governments neglect their interests. Which has led to periodically re-emerging efforts at creating a new state between the two that it’s stuck between.

White supremacists have worked to exploit these grievances, injecting the movement for a hypothetical “State of Jefferson” with a West Coast neo-Confederate ideology. (Truthfully it was always compatible with those kinds of ideas, since the State of Jefferson is named after the president behind the Indian Removal policy.) And there’s evidence that the organized far right sees the Cascadia quake as an opportunity to gain power. It’s already presenting itself to the communities threatened by this event as something they can turn to for help. Neel describes how “Patriot” militias have

…offered preparation workshops for the earthquake predicted to hit the Pacific Northwest and “also volunteered for community service, painting houses, building a handicap playground and constructing wheelchair ramps for elderly or infirm residents.” While often winning the hearts and minds of local residents, these new power structures are by no means services necessarily structured to benefit those most at risk. The Patriot Movement surge in the county followed a widely publicized campaign to “defend” a local mining claim against the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) after the mine proprietors were found to be out of compliance with BLM standards. This sort of vigilante protection of small businesses, local extractive industries, and property holders (in particular ranchers) is often at the heart of Patriot activity.

Today’s left has responded to developments like these by concluding that the rural masses are inherently reactionary, and that socialists are therefore better off ignoring them—even if they experience a 9.0 earthquake. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. The ones in charge of the workers movement have ceded the countryside to the reactionaries, and then interpreted the outcome (success for the right) as confirmation that they’ve been correct to abandon these places. Racism and settler-colonial extractivism have been strengthened throughout the rural areas partly due to the arrogance of the main political actors who claim to oppose these things.

The economic and social breakdown of rural America is a test for where communists want to take their operations. Will they simply let these places continue to decline? Or will they embrace the communities which liberals have forsaken, and thereby gain a great new advantage in the class war?

——————————————————

These right-wing militias, and the ideological elements which share their view of the world, are operating under the assumption that we in the rural areas can only expect to see our connections to the rest of the globe continue disappearing. They share monopoly capital’s hatred of China (something that’s especially reprehensible in my county, where the settlers committed ethnic cleansing against the local Chinese population). And because they’re anti-China, they see a closed-off future. They can’t envision a scenario where our civilization ends its own imperialist parasitism, and collaborates with China to advance infrastructural and technological progress. This pessimistic view of humanity’s future, where supposedly we’ll remain divided along geopolitical barriers forever, reinforces their sense that the solution is to regress. To make our region more resemble what it was like in the 19th century, when whites used paramilitary violence to extract wealth from indigenous lands.

This effort by the lower levels of rural capital to increase primitive accumulation, where capitalists gain wealth by directly taking natural resources, can only continue if capital’s higher levels continue to dominate. The monopolists have engineered rural America’s slow-motion collapse, and have thereby made it inevitable that capital’s smaller elements would deploy their fighting wings to enable greater extractivism. There’s no future in this societal model. It’s a civilization eating itself, with an emerging neo-feudal class coming to dominate the ruins of a long-deindustrialized continent.

We can only rebuild, and progress to a new stage, by ending the imperialist system. Which entails both rectifying the colonial contradiction within U.S. borders, and building connections with the civilizations which our imperialist government wants us to hate. The ending of corporate exploitation of indigenous lands goes along with the effort to end the new cold war, and to bring China’s Belt and Road Initiative to this continent. The BRI can let us construct great new infrastructure, like it’s already done for so many other places around the globe. It can help generate wealth for the communities, whether indigenous, black, or white, that have been driven into poverty by monopoly capitalist rule.

Many of the metropolitan-focused Marxists understand this on an intellectual level. The problem is that they view the bulk of the rural population as inherent enemies of the tribal communities, and as incompatible with the broader communist movement.

Cascadia could show more clearly than ever why holding this view is counterproductive. We already have more than enough evidence to refute it, though. Simply look at the material reasons behind why the white working class has come to “vote against its own interests,” as the liberals accuse it of doing. According to the community organizer Kirk Noden, white workers don’t truly do this, because the Democratic Party has proven itself to hold no value to them. Wrote Noden in 2016:

The impact of this betrayal on white working-class people was a universal distrust and dislike for institutions—none of which were able to defend their livelihoods or their futures. The unions didn’t stay around to organize a new strategy for revitalizing Youngstown. They moved to another line of defense elsewhere, as they grew increasingly insular and focused on protecting their shrinking base…Deindustrialization was a traumatic experience for white working-class people. Yet we act surprised when this constituency exhibits post-traumatic-stress disorder. And it is we who perpetrate the myth that they are voting “against their interests,” despite all the facts on the ground indicating that for them it makes no difference which party is in power. They have lived through 40 years of decline. De-industrialization was a traumatic experience for white working class people. Yet we’re surprised when this constituency exhibits PTSD.

This tells us that a large and growing number of white rural Americans are compatible with an effort to end colonial relations. Because capitalism and colonialism are inseparable, and capitalism is what’s behind these people’s suffering. There are enough of these kinds of whites that when our revolutionary crisis reaches its most intense phase, we rural communists will be capable of beating back the right-wing militias. It depends on whether we’re willing to give up the inward-focused practices which define what “leftism” has become, and expand our efforts into every part of the population that has revolutionary potential.

We know that such an effort to defeat the rural white supremacists can work for two reasons. Firstly, these supremacists aren’t seen by the ruling class as the optimal types of counterrevolutionary fighting forces. At this stage, the state is instead seeking to cultivate anti-communist paramilitary activity among radical liberals, in the form of militant left anti-communist groups like “Antifa.” The state recognizes that these “anti-fascist” groups are better able to be sold to the public as heroes, because using the right for its paramilitary violence would simply discredit the state. This makes the small town right-wing militias, which have already been getting increasingly hostile towards the federal government since the 1970s, less likely to receive backing from the highest levels of capital. We can take advantage of this infighting between these two wings of the colonial apparatus.

Secondly, there’s a long history of white workers joining with anti-racist efforts once they’re shown why class solidarity is in their material interests. Hy Thurman, a veteran of the Black Panther-allied Young Patriots organization, has described how his circle was able to overcome racist indoctrination: “we [the Young Patriots] made the statement, ‘Go and organize your own.’ You know, we don’t need you in Berkeley and other places trying to organize us. We’ll do it ourselves. So you go in your own neighborhood because that’s where the racism exists—and you have to understand that we were racist. I mean, we were raised in racism. It was indoctrinated in us. We were raised racist, but we were becoming antiracist because we began to see what was happening during the Civil Rights Movement. And we began to learn about stuff like Blair Mountain and about the Highlander Center in Tennessee and Miles Horton and the Bradens and those folks.”

This is how the workers struggle can rescue itself from the stagnation which the insular left has brought to it: build a mass base independent from the exclusionary academic and metropolitan spaces that the struggle’s gatekeepers inhabit. These liberal-aligned recent iterations of the socialist movement have succeeded at impeding the cause throughout the era of neoliberalism, and that’s led to a self-reinforcing cycle of hopelessness. But we can end this cycle by reconnecting the movement to the revolution-compatible parts of the masses which exist outside that activist bubble. These overlooked elements are increasing in their number, and in their willingness to fight monopoly capital.

——————————————————

As Neel concludes, the ways in which the rural elements have been reacting to the U.S. empire’s internal collapse are unpredictable. And that’s what the communist movement needs to understand in order to restore its ties to these areas: it’s absolutely not a guarantee that they’ll all fall to the right-wing militias. To what extent they do depends on whether we’re willing not to abandon these communities during the most chaotic phases of the empire’s breakdown. This will be a crucial thing which determines the failure or success of the workers revolution on the North American continent. Because if we allow the liberals to divide the urban and rural revolutionary masses, both parts of the masses will lose to the ruling class.

Refusing to abandon rural America means two things: 1) devoting a proportional amount of energy and resources towards organizing in the countryside compared to in the cities, and 2) giving up the modern conventional leftist practice of seeking only to appeal to Democrats. When a communist signals that they’re only interested in recruiting liberals, they’re showing they don’t want to solve the problem of communism being isolated to the big cities and college towns.

To become effective, we must recognize that investing ourselves in the areas which today’s conventional leftism has forsaken is an essential part of realizing all the goals of our social movements. One subset of the far left that Neel ridicules is the “decolonial” left, not because liberating the First Nations isn’t important but because this ideological element has ironically made itself an impediment to that goal. However noble its cause is, it’s taken on an insular form that makes it unable to gain support beyond the radical liberal niche. By helping ensure the continued confinement of the communist movement to the liberal hubs, and underestimating the potential of the urban masses, this strain works to strategically weaken the same colonized rural communities which it aims to free.

Without an alliance between all revolution-compatible parts of the masses, the indigenous tribes are going to be left more vulnerable to the right-wing militias. The working class movement throughout the rural areas will be unequipped to defend from these militias, because the left’s neglect for the rural masses will have left the movement essentially nonexistent throughout these places. So the reactionaries will fill the power vacuum, leaving those they threaten with no choice but to flee. The irony is that this won’t be because the bulk of rural whites are going to join with the reactionaries. As Neel assesses, most of these whites aren’t even especially receptive to the far right. It will be because the “left” has refused to do its job. Observes Neel about how marginal the far right’s successes at winning poor whites have truly been:

If white ruralites were as inherently conservative as the average leftist would have us believe, they should be flooding into far-right organizations in unprecedented numbers, demanding a platform for their racial resentment. But the reality is that, whether left wing or right wing, political activity is something that is built, not something that emerges naturally from the experience of oppression—this experience only places the success of political organization along a probabilistic curve and colors the character of its result. The far right has only been capable of attracting newcomers in rural areas in a spare few locations. Much of their apparent support base comes either from historical strongholds—such as the KKK counties of the South and those areas of Idaho, Montana, and Washington where white supremacists relocated in the 1990s—or from whitening exurbs…in order to attract new recruits, the far right has had to tone down its explicit racism and foreground economics. But even this has been met mostly with apathy and wariness. The white population of the far hinterland still seems to find more promise in opiates than politics.

It is possible to prevent that outcome where the workers lose the class war while right-wing paramilitaries take over a collapsed rural America. But it will require breaking from the activist circles which are hostile towards the ruralities, and adopting a synthesis that’s truly reflective of our conditions. That brings us to a balance on how much we prioritize the urban and the rural. I emphasize the revolutionary potential of the rural masses not because they’re the biggest part of the people who have such potential, but because we must combat the idea that they don’t matter to the workers’ struggle.

The left-liberal activism industrial complex has used the vilifying narratives about the rural poor both to divide the masses, and as an excuse for the stagnation of these activist groups. The elements of the left which Neel talks about aren’t just disinterested in engaging with or understanding the communities outside the liberal zones. They also don’t seek to build an effective working-class force within the urban areas themselves, as shown by how they’ve pursued adventuristic tactics and worked to sabotage anti-imperialist coalitions. The goal of the American socialist movement’s default leadership is to maintain a monopoly over a particular political niche. Which will inevitably make the communist movement—and all of its related causes, like the pro-Palestine efforts—fail to have a substantial impact.

If this model hasn’t worked, then we must embrace a new one. We must bring back the mass-centered practices that defined both the Panthers in the cities, and the Young Patriots in the small towns. And we don’t have to wait for a massive earthquake or further climate disasters to do this, the people are being subjected to something unbearable as is. It’s our shared catastrophe, the catastrophe of capitalism. We can end it by acting like it’s a collective problem, instead of only focusing on certain victims at the expense of others.

————————————————————————

If you appreciate my work, I hope you become a one-time or regular donor to my Patreon account. Like most of us, I’m feeling the economic pressures amid late-stage capitalism, and I need money to keep fighting for a new system that works for all of us. Go to my Patreon here.

To keep this platform effective amid the censorship against dissenting voices, join my Telegram channel.