Since Che Guevara wrote Guerrilla Warfare, his findings on how an irregular army can wage war against a conventional army, military technologies (as well as civilian technologies) have changed in ways that render his conclusions in need of being updated. His strategic ideas are still broadly correct, but if he were to write Guerrilla Warfare today, he would need to alter its tactical details. Such is the assessment that can be gleaned from studying recent successes in irregular warfare, such as the victory of the Houthis in Yemen over the Saudi coalition.

The Houthis: a case study in irregular warfare against a modern conventional military

Two years ago, it was already apparent that the Houthis were on their way to victory. And Michael Horton of the Jamestown Foundation observed the ways that in order to reach these advantages, their tactics have had to differentiate from the tactics used by guerrillas in previous eras. As he observes, they’ve even seemingly thought about what the future of warfare will look like:

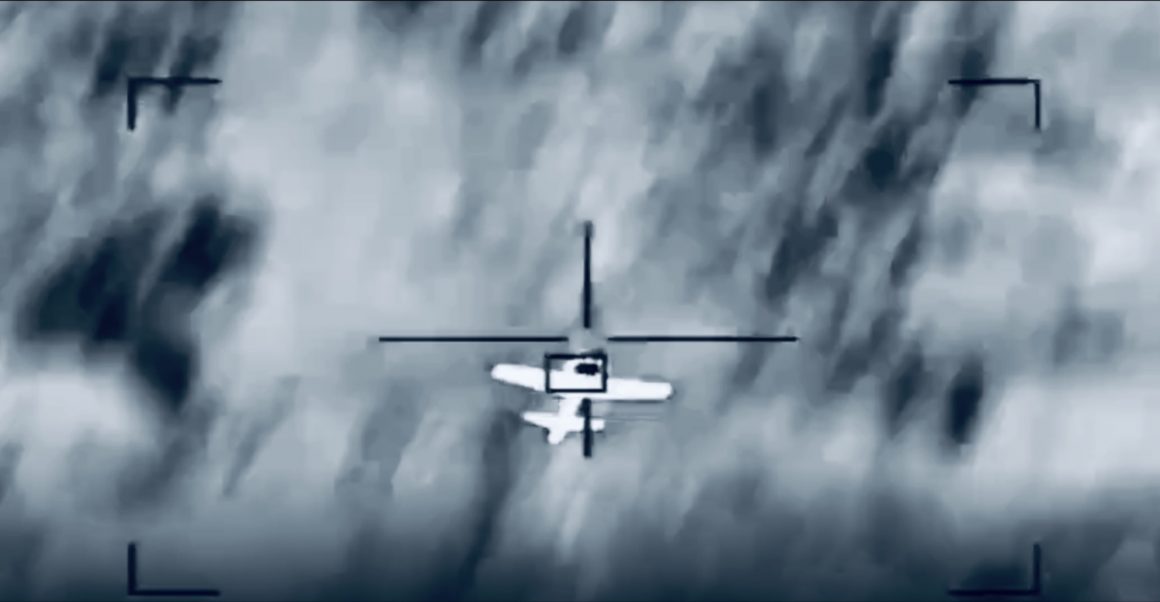

Force mobility has been—and remains—fundamental to the Houthis’ success in battling elements of the Saudi and Emirati militaries as well as those forces they support. These forces include Yemen’s internationally recognized government-in-exile, led by President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, which is allied with Saudi Arabia, and a panoply of militias and armed groups supported by the UAE. The Houthis understand and readily apply what Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley explained in 2016, “on the future battlefield, if you stay in one place longer than two or three hours, you will be dead.” General Milley made his comments in light of the widespread use of drones and other rapidly developing battlefield technologies.

These technologies aren’t just aerial surveillance devices. They extend all the way down to mobile phones, tablets, landlines, and the other everyday items that governments can use to intercept communications. In places like Israel’s imprisoning barrier around Gaza, and the U.S. settler state’s border with Mexico, governments also use surveillance towers that monitor anyone outdoors within a radius of several miles. Horton describes the tactics the Houthis have adopted in response to these new warfare tools as:

-The extensive use of highly mobile units of combat. These units are small, consisting of no more than 20 fighters in two or three light trucks and/or technicals. Because these vehicles are easy to disguise, and can easily traverse Yemen’s most difficult roads and tracks, they’re essential for the Houthis’ ability to evade and harass the enemy. The truck models they use are extremely common throughout the region, and they don’t have to conceal their weapons since guns are a typical item for men in Yemen to carry.

-Even smaller groups of fighters to go along with the main ones. They’re the equivalent to a fire team—typically four soldiers—and they’re tasked with harassing the enemy as well as collecting intelligence. They’re relatively independent, able to operate for weeks with minimal resupply and not typically assigned with daily or even weekly orders from their superiors. Therefore, they usually rely on the creative instructions of their own commanders. They’re given a remit—a task broadly assigned to them—that lasts until it’s canceled. Within these parameters, they take advantage of whichever opportunities for harming the enemy that they can find, operating in clandestine and therefore not easily detectable ways when necessary.

-A policy of keeping electronic communications to a minimum, or using alternative tools for exchanging information. The electronics they do use are not ones that the enemy can intercept. A common Houthi communications device is the phone from the company Thuraya, which says about its product: “With no fixed infrastructure or user configuration mandates, the portable solutions ensure flexibility and can automatically establish an encrypted, secure-link connection within minutes.” They’re a more long-reaching version of items like Beofeng radios, which could theoretically be useful tools for guerrillas but which only offer signals over a few miles depending on the terrain.

-Exclusively uniting their units into a mass when a threat appears that requires the combined strength of more than one unit. They’re only able to coordinate such operations through an extensive intelligence network whose members gather information on enemy movements, proposed routes for counterinsurgency attacks, and other targets. They then pass this information on to Houthi commanders charged with carrying out the attacks, and the units use a combination of human intelligence and drones to track what they aim to attack. When the targets reach an optimal point for attack, the units converge to subdue the enemy, then immediately go their separate ways.

-The use of semi-autonomous units, at least when operating deep in the enemy’s territory. The units in these areas operate their own human intelligence sources, tasked with identifying those targets. Their autonomy makes them nimble, and able to minimize electronic communications (the Thuraya phones are mainly reserved for the highest level Houthi leaders). It also lets them carry out a given attack while requiring little or no chain of command.

This human intelligence aspect is crucial to the success of the Houthis, because as Horton assesses:

Via their extensive network of informants, the Houthis often know more about the location and capabilities of enemy forces than the general officers charged with commanding them. Despite their enemies’ superior weapons, air support, and persistent overhead surveillance, the Houthis routinely anticipate and thwart offensives and counter-offensives. This is primarily due to the human intelligence that they receive from informants across Yemen. The Houthis’ use of numerous types of modified and indigenously produced UAVs [unmanned aerial vehicles] allows them to confirm and augment the intelligence generated via informants. The pairing of human and UAV generated intelligence combined with the Houthis and their allies’ intimate knowledge of Yemen’s rugged mountains and canyons, acts as an effective force multiplier. The Houthis often anticipate the moves made by their foes and respond with deadly force. The accuracy of their responses means they are often able to “arrange the minds of their enemies” by eroding morale and undermining trust in the officers and commanders who lead the opposing forces.

This is consistent with Che’s recommendation that irregular forces carry out sabotage of infrastructure and assassinations of prominent counterinsurgency figures to demoralize the enemy, and to shake the people’s faith in the enemy’s authority so that a transfer of authority can be made easier. But if the Houthis were to simply replicate Che’s tactics, they wouldn’t be able to achieve these ends.

Keeping Che’s strategy, changing his tactics

The Houthis follow the broad strategy explained in Guerrilla Warfare: the rebels work to keep their units perpetually hidden from the enemy so that any conventional battles are avoided, prepare themselves to relocate their camps at any given moment, use ambushes and sabotage to always take their enemies by surprise, and break up their units so that the enemy can’t so easily subdue them. One of the major strategies Che took from this model was to send around six fighters each to surround the enemy from the four points of the compass, then alternately engage the enemy from these points so that they can exhaust the enemy with minimal losses for themselves. This can still work for the Houthis, and for any other given guerrilla army. But the new tactics the Houthis have had to adopt in order to survive show that Che’s military theory must be modified according to the technologies which have appeared since he wrote Guerrilla Warfare in 1961.

The most obvious difference between what worked for him and what works for modern guerrillas is the frequency with which the insurgents need to change their location. Even though Che stated that guerrilla bands must always be ready to move, he left room for the idea that guerrillas can establish static bases in the right conditions:

In the first place, there are only elastic positions, specific places that the enemy cannot pass, and places of diverting him. Frequently the enemy, after easily overcoming difficulties in a gradual advance, is surprised to find himself suddenly and solidly detained without possibilities of moving forward. This is due to the fact that the guerrilla-defended positions, when they have been selected on the basis of a careful study of the ground, are invulnerable. It is not the number of attacking soldiers that counts, but the number of defending soldiers. Once that number has been placed there, it can nearly always hold off a battalion with success. It is a major task of the chiefs to choose well the moment and the place for defending a position without retreat.

This is arguably still true, but it’s now far less often true. In the new era of warfare that Milley described, static warfare is less of an achievable task than ever for guerrillas, and at a certain point it will become essentially impossible—at least in the stages where a guerrilla force hasn’t yet gained control over the state and its military bases. This is the implication of the trend that the European Army Interoperability Centre has assessed is coming about from military drone advancements, and from progress in remote control ground vehicles:

UAVs/UGVs [unmanned aerial vehicles and unmanned ground vehicles] are currently deployed mainly for intelligence, reconnaissance, and surveillance (ISR) missions. Systems such as the “Ironclad (UGV)” or the “Black Hornet” (UAV), are notable examples of this use. However, some are used for combat missions such as the “MQ-9 Reaper/Predator B” (UAV) used mainly by the United States of America (USA) and Israel. Collaboration between these systems in Land Forces is growing closer as UAVs and UGVs are armed progressively. While UAVs assist ground forces by attacking high-value, fixed targets, UGVs can transport explosives and supplies such as heavy weapons or additional ammunition for ground troops, and by providing real-time video surveillance capabilities. This increases the combat power of ground troops by reducing their physical load. Currently, UGVs are not as well-known as their UAV cousins, but they are acquiring more importance as time passes, and their equipment improves. As stated by Major David Moreau of the US Marine Corps, “armed UGVs will one day fight alongside war-fighters during combat operations”.

These new factors—nearly limitless potential for surveillance in warfare and greatly reduced need for humans in combat—have changed the tactics that are appropriate to practice alongside Che’s strategy. The irregular forces of the near future will need to go into battle with a mindset of intensive mobility, even compared to the one that Che recommended. The Houthis have pre-empted the scenario Mills described—of constantly having your operations urgently jeopardized—by changing the fundamentals of how they play the game. They’ve taken Che’s statement that “As the circumstances of the war require, the guerrilla band can dedicate itself exclusively to fleeing from an encirclement which is the enemy’s only way of forcing the band into a decisive fight that could be unfavorable,” and applied it proportionately to the circumstances of modern military surveillance technology.

This sounds like modern warfare tools have purely made irregular warfare harder. But there’s another side to the story: it’s also given irregular forces more tools to utilize. The only reason why a guerrilla force is technologically inferior to a conventional force is that it hasn’t yet had the time to seize the territories, and therefore the weapons, of the conventional force. Che explained that the weapon supplies of the guerrilla are sustained through its enemy, and that tools like the bazooka aren’t attainable for the guerrilla until they can get seized from the enemy. Irregular warfare is not a game of trying to destroy society through a limited supply of weapons, but a game of taking control over society’s facets—whether its armaments, its infrastructure, or its informational sources. Che describes how the guerrillas must seize the enemy’s radio networks of a given area in order to provide information about the war to the locals, and to therefore ensure social cohesion within the liberated zones. In the modern era, the equivalent must be done when it comes to the enemy’s military technologies, allowing the irregular forces to themselves utilize drones for surveillance and attacks.

Such is the new language that today’s military analysts must translate texts like Guerrilla Warfare into. A language that accommodates not just the invention of drones, the emergence of monitoring tools like the Gaza towers, and the imminent advancements in remotely controlled ground vehicles, but the invention of the internet, mobile devices, and social media. With these factors, insurgents have many more vulnerabilities towards surveillance to avoid, especially if they operate in a clandestine fashion.

In his section on suburban warfare, about the prospect for insurgents to infiltrate the communities controlled by the enemy, Che describes a lifestyle that was naturally difficult to maintain: “If there is more than one guerrilla band, they will all be under a single chief who will give orders as to the necessary tasks through contacts of proven trustworthiness who live openly as ordinary citizens. In certain cases the guerrilla fighter will be able to maintain his peacetime work, but this is very difficult. Practically speaking, the suburban guerrilla band is a group of men who are already outside the law, in a condition of war, situated as unfavorably as we have described.” Today, when the internet is integral to academic work and professional life, such a balance between civilian life and insurgency life is even less feasible. Therefore this kind of approach needs to be reduced, as attempts at static warfare need to be reduced. The Houthis have shown that suburban warfare and spy work are still doable, but that those involved must forsake the tools that make modern life functional.

The qualifier is again that this new technological context doesn’t necessarily make irregular warfare harder, as the internet has given unprecedented weapons to insurgents. If Guerrilla Warfare were written today, it no doubt would delve into hacking, online informational warfare, and cybersecurity tools, like the ones the Houthis use. Insurgency hasn’t become harder, it’s just become more complicated.

Like how pieces of military theory must be interpreted while acknowledging that different places have different social, cultural, or geographical conditions, the differences in eras must be taken into account. Technological progress has fundamentally recontextualized what Che’s theories mean. He wasn’t wrong in his historical context (at least outside of his mistaken conviction that Cuba’s insurgency model could be replicated throughout the rest of Latin America despite the differing conditions). But faced with these changes to how war is waged, even his most useful insights need to be read through an updated lens.

—————————————————————————

If you appreciate my work, I hope you become a one-time or regular donor to my Patreon account. Like most of us, I’m feeling the economic pinch during late-stage capitalism, and I need money to keep fighting for a new system that works for all of us. Go to my Patreon here.